Shakhnoza Kasymova,

Art Critic

At present, there are many views on how the nature of visual art should be understood. These views are largely defined by cultural traditions, by a kind of a ‘genetic code’ in art and contemporary art situation. One of these points of view suggests that visual art is one where an ornament built on plasticity is refracted in a particular way. It is no accident that all over the world it is referred to as PLASTIK ART. The beauty of form and content is perceived as flesh and soul of visual art. Its objective is the ability to beautifully organize a surface before the artist (paper, canvas, wall…) through a set of shapes, strokes and colour, and every time for a contemporary artist reaching this goal presents a problem in the primacy of synthesizing shapes and strokes.

At present, there are many views on how the nature of visual art should be understood. These views are largely defined by cultural traditions, by a kind of a ‘genetic code’ in art and contemporary art situation. One of these points of view suggests that visual art is one where an ornament built on plasticity is refracted in a particular way. It is no accident that all over the world it is referred to as PLASTIK ART. The beauty of form and content is perceived as flesh and soul of visual art. Its objective is the ability to beautifully organize a surface before the artist (paper, canvas, wall…) through a set of shapes, strokes and colour, and every time for a contemporary artist reaching this goal presents a problem in the primacy of synthesizing shapes and strokes.

In the early twentieth century artists in Europe turned to the enigmatic and mysterious heritage of the East. Instead of classical imitation and copying, they created a new means to represent reality, having developed plastic art, that is, “notions, imaginings, illusions”, consisting of ornamental patterns. Without conceptualizing and explaining all the revolutionary transformations that occurred in the last century in the world of painting, it is impossible to understand the very nature of visual art. Searching for new means of expression, and identifying plasticity in nature and art guided many an artist in their creative quest.

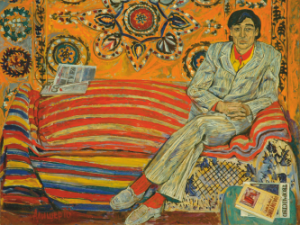

People’s Artist of Uzbekistan, Academician of the Academy of Arts of Uzbekistan Alisher Mirzaev is a master of contemporary Uzbek visual art who turned his keen eye toward traditional national values and discovered his own imagery and plasticity; he has taken closely to heart the music of oriental shapes and brush-strokes, eagerly exploring artistic heritage and new means and methods of expression.

Already in his student years, the artist sought to express national flavour in his compositions, employing decorative colour and plastic solution founded in traditions (miniature paintings, ancient murals, traditional applied arts). Reminiscing about his years of study at the Moscow Art Institute named after V. I. Surikov, the master gratefully recalls the words of his mentor A. M. Gritsai: “Alisher, you should use one eye to see and learn Russian fine art, and the other one to study the culture of the East.”

This idea found proof in the artist’s student works: “Buvim” [“My Grandmother”] and “Kuk Bozor” [The Green Market]. Performing coursework assignments in line with the canons of classical miniature (two-dimensional surface) and traditional applied arts (colour fort, decorativeness) in a school that followed the traditions of Russian fine art was a daring step on the part of young Alisher in those days. Also progressive was the role of his mentors who supported the young painter in his aspiration to create freely. Alisher Mirzaev’s interest in ancient cultural heritage, as well as impressions of his childhood spent in the Old City part of Tashkent saturated with bright colours, prompted him to create unusual paintings. Flatness of oriental miniatures, the colour palette of traditional decorative art and a certain rhythmic pattern inspired the author to create complex multi-subject compositions on canvas, containing large space and rhythmically reinforcing its peculiar architectural look.

This idea found proof in the artist’s student works: “Buvim” [“My Grandmother”] and “Kuk Bozor” [The Green Market]. Performing coursework assignments in line with the canons of classical miniature (two-dimensional surface) and traditional applied arts (colour fort, decorativeness) in a school that followed the traditions of Russian fine art was a daring step on the part of young Alisher in those days. Also progressive was the role of his mentors who supported the young painter in his aspiration to create freely. Alisher Mirzaev’s interest in ancient cultural heritage, as well as impressions of his childhood spent in the Old City part of Tashkent saturated with bright colours, prompted him to create unusual paintings. Flatness of oriental miniatures, the colour palette of traditional decorative art and a certain rhythmic pattern inspired the author to create complex multi-subject compositions on canvas, containing large space and rhythmically reinforcing its peculiar architectural look.

“National artistic heritage, traditional arts and crafts, and classical miniature influenced the artist markedly. In traditional art the painter discovered a whole new world, amazing in its colour combination, composition and melody, outstanding in the harmony and beauty of its imagery and shapes – something that was originally akin to the spirit of the artist”, noted Kamola Akilova, Doctor of Art History.

Alisher Mirzaev very early discovered the ‘national’ perspective in art, which was characteristic only of him; partaking from the world’s heritage, he was looking for ways to express the ‘national’. As an epigraph to a catalogue of his first solo exhibition held in 1982 the artist chose the words of the famous Armenian painter Martiros Saryan: “At first I was enchanted by the fabulous beauty of nature. It was imperative to find forms and means through which I could at least in some way express these overwhelming emotions. To do this, first, I had to completely free myself from the influences of superficial, sticky traditions so deeply rooted in my mind, and then, without exploiting what others have found, create my own individual signature. For a proper visual portrayal of events I started searching for simple yet stable forms and colours. All in all, my objective is to attain maximum efficiency and effectiveness, and, specifically, to get rid of the halftones that prompt you to compromise. What I had in mind was the great power of morphogenesis and the sensation of being heavenly in love, which is common to all art forms, from olden times to the present day, and which has always been attained differently” (1, p. 7). Of the Uzbek artists, this process shows in the art of the People’s Artist of Uzbekistan Chingiz Ahmarov who already at a young age was exploring the problem of ‘national’ in visual art, and his paintings on the walls of the Navoi Opera and Ballet Theatre in Tashkent became a prologue to the painter’s subsequent successful discoveries.

As early as in his student years, Mirzaev, too, set an ambitious goal for himself. Chingiz Ahmarov encouraged his aspirations, and, looking at his works, noted: “Compared to your age peers, you have chosen a path too challenging, and walking it is not going to be easy, but I have faith in you and in your strength!”

As early as in his student years, Mirzaev, too, set an ambitious goal for himself. Chingiz Ahmarov encouraged his aspirations, and, looking at his works, noted: “Compared to your age peers, you have chosen a path too challenging, and walking it is not going to be easy, but I have faith in you and in your strength!”

Mirzaev looked for a synthesis of regularities in Western fine arts and the new eastern Uzbek national visual art, a proportionality between the best and effective advantages of these two worlds; thus his art became a natural process, in which one could identify different stages and innovations.

A catalog-album released on the occasion of Alisher Mirzaev’s anniversary exhibition in the National Arts Centre evidences the fact that he pursued two different directions in parallel (2, p. 6).

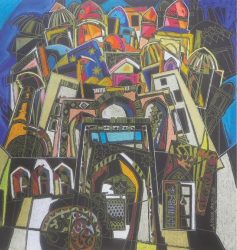

The artist’s works, from his debut until today, demonstrate that the notions of Western and Eastern visual art somewhat align. In this regard, quite characteristic are his paintings from the Tashkent series: «The Tashkent Still-life» (1982), «Self-portrait Still-life» (1982), «Tashkent, the City of Peace and Friendship» (1982-1984); the Sukok series: «Meeting at the red breach» (1987), «The Sukok Mosaic» (1987), «Golden House» (1988); the Humsan series: «Commemorative Prayer» (1977), and «Humsan. Autumn care» (1997). Constructive shapes of ornamented paintings harbour a cosmic element.

Fates so willed that Mirzaev found his creative laboratory in the village of Sukok situated in the Parkent District of the Tashkent Province. The beauty of Sukok with its mountains and hills, holiday homes, waterfalls and streams, orchards and vineyards offered an inexhaustible source of inspiration for the artist.

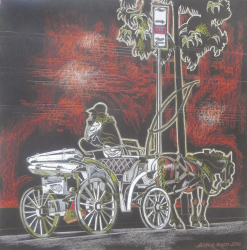

In the early 2000s the artist developed an interest in miniature painting and traditional arts and crafts; his canvases show ornamental surface, two-dimensional space and decorativeness of colour.

In 1903-1905 dramatic changes occurred in the major cities of Europe, such as Munich, Berlin and Paris, following a Kamoliddin Behzad exhibition displaying twenty original paintings of the famous miniaturist. Many leading European painters turned their eye to the East, abandoning the traditions of the Old Dutch school. Henri Matisse, the founder of fauvism that was a new trend in painting, who had achieved plastic ornamentalism of colour in his art, proclaimed Kamoliddin Behzad his mentor, admitting that for him “all innovations come from the East” (3, p. 20).

A century later, Alisher Mirzaev, the Uzbek artist and our contemporary, again demonstrates a constructive approach, architectonics, and traditional art of carving.

Romantic touch, geometrical proportions and deep philosophical meaning inherent in Islamic painting (miniature) are reflected in the works of applied art and painting. The artist who believes vegetable motifs and girih grid patterns to be the foundations of plasticity in all forms of fine art rationally employed the regularities of plasticity in his art. In his paintings “Two Tambourines” (2008), “The Doll” (2008), «Faire bird» (2008), «Bright Still Life» (2007) and “Pomegranate Juice” (2007) one can see the synthesis of geometry and constructivism, airy designs and brushstrokes.

Mirzayev believes that in a constructive ornament “compositions are structured similarly to an exact science, with an uninterrupted proportion of form and colour on the composition plane. Inspired effort of a creator can be compared to the work of a scientist. A painter before a canvas-space, like a mathematician searching for solution to a problem, goes through countless combinations of shapes, brushstrokes and colours. Perfection and beauty of the product depend on the beauty and precision of the found answer, on the elegance of the solution”.

In his «A Girl from Sukok» (2012), «A Bride» and «Pomegranates» (2013) the artist remains true to himself and his principles: based on his understanding and regarding pieces of visual art as a means of modern interior decoration, he strengthens their decorative element, distance and proximity of double projection, and harmony of strokes. In his “Pomegranate”, the compositional solution on a plane is based on the possibilities of applied arts and crafts, as well as on traditions and regularities of Uzbek embroidery. One gets an impression that the painter draws on the art of carving and its ornaments.

In his «A Girl from Sukok» (2012), «A Bride» and «Pomegranates» (2013) the artist remains true to himself and his principles: based on his understanding and regarding pieces of visual art as a means of modern interior decoration, he strengthens their decorative element, distance and proximity of double projection, and harmony of strokes. In his “Pomegranate”, the compositional solution on a plane is based on the possibilities of applied arts and crafts, as well as on traditions and regularities of Uzbek embroidery. One gets an impression that the painter draws on the art of carving and its ornaments.

In November 2013 an exhibition called “Ornamental World of Alisher Mirzaev” presented series of his works dedicated to places such as America, Samarqand, Bukhara, Sukok, and to the writer Abdullah Kadiri, – the product of his daring effort of many years. Poetic approach and originality of compositional plastic solutions prove that Mirzaev’s art reached its heyday, with every successive exhibition being a surprise and delight to the experts and admirers of his talent.

References

1. Мюнц М. В. Алишер Мирзаев. Каталог. 1982.

2. Алишер Мирзо. Альбом. Ташкент, 2008.

3. Абдуллаев М. Бехзод и Матисс // Творчество, 1976, № 6.