Shoira Nurmuhamedova,

Architect

Freemason of science – this is how Galina Anatolyevna Pugachenkova, a world-famous scientist, referred to herself. She is known for her invaluable contribution to science as architect, archaeologist, art historian, and numismatist. Personality and multifaceted talent of this legendary woman, “innovator in all areas of science”, was greatly influenced by her father Anatoly Pugachenkov, a learned man and brilliant engineer who worked as an architect in the city of Verniy (now Almaty). Emotional bond between father and daughter was maintained through correspondence and gifts such as books. Pugachenkova inherited from her father an interest in natural sciences, literature, languages and arts in general, as well as her legendary indefatigable industry, willpower, perseverance, drive and endurance.

Freemason of science – this is how Galina Anatolyevna Pugachenkova, a world-famous scientist, referred to herself. She is known for her invaluable contribution to science as architect, archaeologist, art historian, and numismatist. Personality and multifaceted talent of this legendary woman, “innovator in all areas of science”, was greatly influenced by her father Anatoly Pugachenkov, a learned man and brilliant engineer who worked as an architect in the city of Verniy (now Almaty). Emotional bond between father and daughter was maintained through correspondence and gifts such as books. Pugachenkova inherited from her father an interest in natural sciences, literature, languages and arts in general, as well as her legendary indefatigable industry, willpower, perseverance, drive and endurance.

In a lifetime we cross path with different people, every one of them to an extent influencing our personal evolution. Galina Anatolyevna was always surrounded by interesting people. Her university teachers were scholars and enthusiasts of Central Asia such as L. N. Voronin, artists Igor Kazakov and F. Schmidt. B. N. Zasypkin, then the chief architect of UzKomStaris (State Committee for Antique Art), introduced a science-based method in restoration work in Uzbekistan. Study, restoration and conservation of monuments became the cause of his life, and the scientist proved to be most professional at it, “infecting” others with his passion and enthusiasm. With Zasypkin’s help many young scholars got an opportunity for a good start of their academic career. Brief meeting with him also guided Galina Pugachenkova in her professional choices.

A life partner for a person like Pugachenkova had to be a man as strongly in love with his work. And such man was Mikhail Evgenyevich Masson: from the late 1930s and for almost fifty years Masson and Pugachenkova were together. Next to him she found her happiness as a woman. Mikhail Evgenyevich, in turn, was proud of his spouse, inspiring her great academic achievements. Masson was her colleague, and his coaching, as Pugachenkova mentioned, made her believe in the power of material. Galina Anatolyevna once said, ‘Both my strength and my weakness is love, and love only”. Great Love united the two people, giving them a powerful motivation to create and make great scientific breakthroughs.

Intellectual and emotional kinship developed between Galina Pugachenkova and Lazar I. Rempel: not only were they friends, colleagues and co-thinkers, but also peer reviewers and co-authors of academic papers, and sometimes even ruthless critics of each other’s work. Their postal “romance” that lasted nearly 45 years helped Rempel stand up to the challenges of life. Themes they discussed included arts, archaeology and architecture. At that time Uzbek art history was still in infancy, so Pugachenkova and Rempel had to fill in many blanks in the history of arts of Uzbekistan. Works they co-authored encouraged new discoveries and provided ground for subsequent academic research.

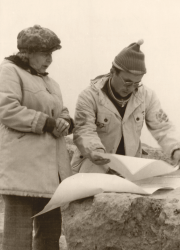

Her determination and resolve based on the experience of earlier field work, in which Pugachenkova actively engaged, and as a result of her strong desire to create the country’s history of arts, the scientist succeeded in organizing Uzbekistan’s comprehensive art history field work unit she lead for more than a quarter of a century. Time had proved it the right decision, as archaeological excavations provided access to the ancient artistic culture of Uzbekistan, bringing its researchers worldwide fame. Fundamentally important was Pugachenkova’s argument in defence of the ‘antiquity’ concept itself as applied to Central Asian culture dating to the first centuries before and after Common Era.

Her determination and resolve based on the experience of earlier field work, in which Pugachenkova actively engaged, and as a result of her strong desire to create the country’s history of arts, the scientist succeeded in organizing Uzbekistan’s comprehensive art history field work unit she lead for more than a quarter of a century. Time had proved it the right decision, as archaeological excavations provided access to the ancient artistic culture of Uzbekistan, bringing its researchers worldwide fame. Fundamentally important was Pugachenkova’s argument in defence of the ‘antiquity’ concept itself as applied to Central Asian culture dating to the first centuries before and after Common Era.

A short article cannot duly cover the scholar’s great contribution to the many fields of science. As an architect, the present author can offer only a general overview of Pugachenkova’s fundamental studies on Central Asian architecture, since these were the ones that opened a science-based phase of research in the history of architecture in the region, that is, with division into periods, analysis, theoretical generalization of archaeological materials, and an integrated approach to the object of study. For instance, appealing to concrete facts, Pugachenkova proved that art (architecture in this case) reached the standard equal to artistic achievements of the ancient Mediterranean. The scientist saw the reason for this in the commonality of ideological objectives characteristic of the ancient worldview. Prior to these studies, no sites had been properly identified to give a good idea about the development of architecture in Antiquity. The discovery of monuments such as palace in Khalchayan, residential buildings at Dalverzintepa, and cult structures in Termez and Ayrtam heralded a new stage in the study of ancient architecture of Central Asia, which developed in parallel with that of Assyria and Babylonia, Achaemenid Iran and the Greco-Roman world. Without refuting that fact that Bactrian architecture was influenced by certain elements of other Hellenistic type nations, as well as by progress made during the preceding Achaemenid period, Pugachenkova advocated the idea of an independent development of Central Asian architecture, believing that local architectural features in that time frame were created by indigenous peoples inhabiting the territory. The scholar identified four main architecture schools in Central Asian Antiquity – Khorezmian, Parthian, Tokharistanian, and Sogdian, having defined the specificity of each.

Galina Pugachenkova did not get carried away by her academic success; rather, her attainments encouraged further scientific exploration with her inherent comprehensive approach and a knack for generalization. As a next step in architectural studies, Pugachenkova took to the medieval period. Referring to the monuments located in Northern Tokharistan, Northern Khorasan, and Transoxiana (a.k.a. Maverannahr), she formulated and then resolved the problem of dating, graphic reproduction and purpose of certain structures; she also identified specificities of the Tokharistan, Khorasan-Dahistan, and Maverannahr schools of architecture. This was important to determine cultural contribution made by Central Asian nations to the evolution of Islamic architecture, since these findings established the advanced quality of new construction machinery, structures, regional planning principles (keshk as examples), and new compositional solutions (Buddhist structures). Two typological groups in medieval architecture were identified: with a courtyard, and with a central hall; these were used in buildings serving different purposes. This means that science has got a clear idea about Central Asia architecture over a millennial period, as well as knowledge about its evolution. Naturally, this research was preceded by the earlier studies of Central Asian architecture; however, no monuments had been properly explored to provide consistent knowledge about the development of architecture in the region.

Besides Antiquity and early Middle Ages, Pugachenkova was also interested in the Timurid architecture: studying it provided a justification for the architectural typology characteristic of palaces, mosques, madrasah, honako, minarets and mausoleums dating to that period. Also, while she argued for the presence of local architectural schools in the earlier periods, then in relation to the era of Amir Temur and Ulugbek Pugachenkova identified a special synthetic style that absorbed the best achievements of the past and was reciprocally enriched with creative ideas sourced from different parts of the great power. Thus, Pugachenkova was the first to focus on issues such as presence of architectural schools in a given period of time, typology, and genesis of different structures. Some of her views and interpretations, naturally, caused controversy and disagreement of other scholars, but still Pugachenkova’s research work guided the science, prompting further study of the disputed ideas.

It is important to note that providing prompt and systematic information on the results of research was one of the core principles Pugachenkova followed in her work. Her papers are still in demand and popular to this day, even when science already has substantive new facts and new materials. One would think that the reason for this, besides the unquestionably high scientific value of her work, is the author’s simple and understandable presentation of numerous archaeological facts often involving complex scientific problems; yet her texts are graspable not only for scholars, but also for a broader audience.

It is important to note that providing prompt and systematic information on the results of research was one of the core principles Pugachenkova followed in her work. Her papers are still in demand and popular to this day, even when science already has substantive new facts and new materials. One would think that the reason for this, besides the unquestionably high scientific value of her work, is the author’s simple and understandable presentation of numerous archaeological facts often involving complex scientific problems; yet her texts are graspable not only for scholars, but also for a broader audience.

Prominent scholar Galina Pugachenkova was a wonderful teacher, too. Her students remember her as a very strict and demanding mentor; a born presenter, she could easily ignite people’s interest. One of her grateful and most famous students is Academician Edvard V. Rtveladze who highly values the scholar’s talent and work, doing a lot to keep the memory of his teacher going. Comprehensively addressing a problem and referring to scientific facts and materials to solve it is an academic approach he learned from his famous teachers – Mikhail Masson and Galina Pugachenkova. According to her, she “had a good fortune to pass the baton to him (Rtveladze – Sh. N.)”, and he has proved worthy of carrying it on.

Pugachenkova always worshiped human genius that created unique works of art; she admired the beauty of the land she studied, and the culture of people inhabiting it… She made it her purpose to communicate it to her reader and listener, and not only in her home country, but also abroad, defending the idea of independent evolution and development of the national culture. Pugachenkova enjoyed life wherever it took her – archaeological field work, taking measurements under the burning sun of Central Asia, at symposia and conferences, in libraries and travels – everywhere she was in her element. A true scientist, weak and strong, serious and ironic, focused and enthusiastic, mysterious and spontaneous – she was a real woman capable of appreciating all things beautiful, including smart dresses and jewellery. Her life path and career in science deserve respect and admiration. We have been fortunate to be contemporaries of this prominent scholar, who, in her own words, “is always in pursuit, craving, anticipating – that is, experiencing the best that life can offer a man…”

References

1. Пугаченкова Г. А. Античность в искусстве Востока и Запада. Центральноазиатский мир и Средиземноморье. К постановке проблемы // Проблемы взаимодействия художественных культур Запада и Востока. Тезисы докладов. М., 1972. Машинопись; К изучению памятников Северной Бактрии // ОНУ, 1968, № 3; Зодчество античной Бактрии – традиции и связи // Античность и античные традиции в культуре и искусстве народов Советского Востока. М., 1978; Искусство Бактрии эпохи Кушан. М., 1979; К архитектурной типологии в зодчестве Бактрии и Восточной Парфии // ВДИ. , 1973, Л. № 1.

2. Пугаченкова Г. А. Зодчество Центральной Азии. XV в. Ведущие тенденции и черты. Ташкент, 1976; К проблеме архитектуры феодального Востока // ОНУ, 1963, № 6; К проблеме средневековых архитектурных школ Центральной Азии // ОНУ, 1998, № 4-5; Роль Бухарской архитектурной школы в сложении типологии ранних мавзолеев Мавераннахра // ОНУ, 1997, № 9-11.

3. Ремпель Л. И. История искусств Средней Азии в трудах Г. А. Пугаченковой // Из художественной сокровищницы Среднего Востока. Ташкент, 1987; Диалоги в письмах 1940-х-1980-х гг. // Архитектура и строительство Узбекистана, 1990, № 2.

4. Ртвеладзе Л. И. Пугаченкова Г. А. и архитектурные реконструкции // Архитектура и строительство Узбекистана, 1990, № 2.