Kamola Akilova,

Art Critic

Design is present in all domains of human activity: architecture and landscape, interior and apparel, objects and expositions… It becomes not just an art form, but a way of living, a world outlook, and a criterion of the society’s aesthetic taste.

As far as design is concerned, what is the situation in Uzbekistan? At the recent roundtable discussion of design-related issues a renowned academic questioned the existence of design in the country. This article aims to shed some light on the matter.

Design as a Theory Problem

Design as a Theory Problem

The classic stance is that design as an art domain emerged in the late 19th century in Great Britain, where the industrial boom was closely linked with the development of capitalism, galvanized market relations, and the need to promote goods in the market. Another conventional wisdom, even among experts, is that design has always existed – almost since the ancient times, manifesting itself in traditional culture.

The cause of controversy over the subject and object of design has been the vagueness of the term itself – a matter discussed as early as the 1970s by V. L. Glazychev (1). Tomas Maldonado understood design as a specific art form founded in rigorous scientific methodology (2). And, legitimately perhaps, G. N. Lola wrote: “Surprisingly, that there is still no general theory of design” (3).

The late 20th and early 21st centuries actualized the issues of design theory and practice, which currently represent a well-developed, extensive and dynamic domain. For many decades, design theory was being elaborated and studied by the West European and American researchers (4). Literature review suggests that presently the history and theory of European and American design is sufficiently studied and the art of design schools well-researched. It was the Europeans who introduced the concept of ‘design philosophy’. According to Tomas Maldonado, “different design philosophies express different attitude to the world. The place we give to design in the world depends on how we understand the world” (5).

Great contribution to the development of design theory was made by Russian researchers (6) who classified all of its forms as follows: (i) design as an objective art; (ii) design of object-and-space environment; and (iii) information design. They consider design as a culture- and civilization-related phenomenon, as a material carrier of life style and mode containing certain cultural meanings (7).

Designed in its contemporary understanding is a project-related culture specifically known to be imaginative, systematic and innovative. It requires professional combination of imagination and system elements, while introducing new socio-cultural semantics into reality.

In the years of independence, the problem of design was also mainstreamed in a number of art history schools in the former Soviet Union. Specifically, Azerbaijan was home to a number of academic research projects in the domain of design theory (8). For Instance, E. Aliev holds that contemporary design is immediately linked to the visualization of culture, which “reflects the underlying processes of change in its meta-language and the transformation of the whole multitude of worldviews: national, social, scientific, and artistic” (9, p. 3). According to Aliev, design is an art form that filled up postmodernist cultural space; it is the reflection of the Western world view, which embodies its archetypes at a late stage of the European culture development. Naturally, besides its artistic imagery, design implies the presence of certain consumption standard, or consumption culture, in other words. The category of form is central to the creation of the design picture (9, p. 124-125).

It should be noted that in the XX-XXI centuries design all over the world is a dynamic phenomenon with science-based theory, different schools, concepts, vectors, and personalities. It has now taken its due place in science, in the life of society, and in people’s minds.

It should be noted that in the XX-XXI centuries design all over the world is a dynamic phenomenon with science-based theory, different schools, concepts, vectors, and personalities. It has now taken its due place in science, in the life of society, and in people’s minds.

Design in Uzbekistan in the XX century

Many theoretical provisions in academic papers on the 20th century design in Uzbekistan allow a completely different perspective on the problem of design in Uzbekistan, whose art culture represents a unique phenomenon synthesizing traditions of the past and innovations of the future, the depth of refined oriental culture and the breadth of the dynamic culture of Europe.

In our view, in the pre-revolutionary period in the art culture development in Uzbekistan, design cannot be considered as a special art form. The region becoming part of the Russian Empire and drawn into the orbit of capitalist relations had changed the society, its traditional lifestyle, culture and art. This was particularly evident in the “European” urban quarters where appeared new transport modes, industries, banks, printing shops, photo studios, schools and lyceums. All these innovations were coming from Europe, or rather in the style of Russian culture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries; they could be seen not only in architectural forms, but also in clothing style, in commercial goods flooding the local market, in photographs, in the first street posts, in printed products… Likely, this was the nascent design in all of the Russian Empire, when market started needing advertisement, and advertisement required appropriate artistry – this time not painting or drawing in the conventional sense, but a design.

Complex social, political and economic situation in the 1920s through 1950s did not favour the evolution of design. Civil war, famine, devastation, political oppression, World War II, efforts to rebuild the post-war economy with the emphasis on the heavy industry development – all this created a different dimension that simply had no room for design. However, during that time a lot of attention was given to public outreach, and art played a role in this process. The 1920s-1930s propaganda engaged L. Bure, O. Tatevosyan, G. Nikitin, A. Nikolaev (Usto Mumin), V. Eremyan, I. Kazakov, I. Ikramov, S. Malt, B. Zhukov and others who were later to become renowned artists. Their efforts laid the ground for the development of graphic design in the future.

Complex social, political and economic situation in the 1920s through 1950s did not favour the evolution of design. Civil war, famine, devastation, political oppression, World War II, efforts to rebuild the post-war economy with the emphasis on the heavy industry development – all this created a different dimension that simply had no room for design. However, during that time a lot of attention was given to public outreach, and art played a role in this process. The 1920s-1930s propaganda engaged L. Bure, O. Tatevosyan, G. Nikitin, A. Nikolaev (Usto Mumin), V. Eremyan, I. Kazakov, I. Ikramov, S. Malt, B. Zhukov and others who were later to become renowned artists. Their efforts laid the ground for the development of graphic design in the future.

In the 1920s and 1930s traditional Uzbek costume, albeit slowly, but adapted to the new situation and the requirements of time. New kinds of apparel, the absence of redundant frills and ornamentation, the forgoing of a scarf over a skullcap for the starters, and eventually of the skullcap itself, the use of factory-made textiles and readymade items – all this gradually became a dominant trend in the costume of that era.

The 1930s and 1940s saw the founding of the textile industry. From the 1930s, apparel industry started meeting large-scale public demand. Western-style clothes became increasingly popular, often incorporating elements of traditional dress that, sadly, was loosing the integrity, historicity, spirituality and content inherent in historical costume. But then it was a response to the changed situation and the life’s pace, the advantage of mass production over cottage industry.

In the 1940s and 1950s apparel design keeps two trends going: European costume with its straight shoulder fitted jacket and slacks for men and a flared skirt, loose-fitting cut bodice and abundant ornamental details for women; and the traditional dress. In the meantime, in some remote provinces people kept wearing traditional clothes of the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. In 1959, The Fashion House opened in Tashkent, marking the establishment of professional art of apparel design.

In the 1960s and 1970s a need to saturate the market becomes relevant. The Iron Curtain slightly ajar exposes the Western bounty, with design industry long since taking the lead. During that time in Uzbekistan large state-owned companies launch the production of furniture, consumer goods and utility items showing the marks of new times. The term “technical aesthetics and design” spreads through the domains of art design in the textile, plant engineering, instrumentation, automotive and other industries. Design in all its forms starts developing more intensively, yet still failing to produce any original solution.

In the 1960s and 1980s apparel design in Uzbekistan evolves in the common pan-Union context, with its key criteria being modernity, appropriateness, and the beauty of a human body highlighted. In Uzbekistan, besides the preservation of traditional costume as such, national traditions are employed in modern apparel design, in the form of selected traditional elements, the use of traditional textiles such as bekasab, banoras, satin… Gold embroidery now adorns formal dress gowns, while satin is at play in modern-day fashion.

Design in Uzbekistan since Independence

Since the Republic of Uzbekistan attained independence, design has become one of the popular forms of artistic expression, helped by market development, the start of numerous small- and medium-sized businesses, galvanized international cultural relations, and information sharing in the society. Moreover, design was mainstreamed into the cultural policy of the young independent nation, as reflected in the government resolutions on the development of design as a discipline (10).

Design began to receive a lot of attention in art education, too. Established in 1997, the National Institute of Arts and Design named after Behzad opened the Faculty of Design with the Fashion Design and Interior Design Departments. For many decades the Tashkent Institute of Textile and Light Industry has trained designers for food and textile industries. Training in the field of design is also provided by the Tashkent State Technical University named after Abu Raihan Biruni, and by the Tashkent Institute of Architecture and Civil Engineering.

Design began to receive a lot of attention in art education, too. Established in 1997, the National Institute of Arts and Design named after Behzad opened the Faculty of Design with the Fashion Design and Interior Design Departments. For many decades the Tashkent Institute of Textile and Light Industry has trained designers for food and textile industries. Training in the field of design is also provided by the Tashkent State Technical University named after Abu Raihan Biruni, and by the Tashkent Institute of Architecture and Civil Engineering.

Uzbekistan holds academic seminars, science-to-practice conferences, workshops and trainings in the field of design, both at the national level, and with the engagement of foreign experts. The Tashkent Institute of Architecture and Civil Engineering has a good experience in cooperating with the University of Versailles (France) and Bauhaus (Germany) in the area of annual bilateral student exchange.

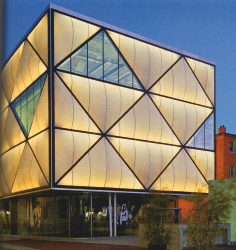

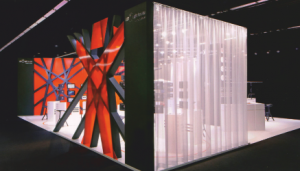

The most advanced design forms in Uzbekistan are graphic, fashion, interior, and landscape design. Festivals and fashion design contests facilitate the emergence of talented apparel designers not only catering to the local market, but also showing their collections on the catwalks overseas. Various international exhibitions, biennials, art projects, and the participation of Uzbek artists in exhibitions abroad have actualized and issues of expo design. With the development of small and medium business, advertisement design has become popular.

Quite interesting are design projects in the area of outdoor urban art. Many innovative ideas come from young people, including graduates of the Tashkent Institute of Architecture and Civil Engineering. Exhibitions they hold present many interesting ideas for the development of urban environment. The problem lies elsewhere: there is no funding to implement theses projects.

Interior design projects often engage painters and theatre set designers, such as B. Ismailov, Merited Culture Promoter, and others.

All in all, the practice of design in Uzbekistan evidences the development of its various forms. Currently ongoing is the process of exploring international experience and learning about design attainments in the world; designers seek to find their own solutions and signature style.

Design Theory in Uzbekistan

Design theory in Uzbekistan, however, is noticeably lagging behind other academic schools in other countries, even in the post-Soviet ones. There are objective reasons for that: undeveloped domain, replication of standard engineering. In our view, this has to do with inadequately studied history and theory of design in universities and vocational schools. Students are taught mostly practical design skills, with less attention given to the philosophy and design concept proper.

Apart from that, design, and especially its theory, is a new area for researchers. For many years the theory of design was not part of research code registers. “Industrial Art and Design” was the academic passport name in the registry of the State Commission for Academic Degrees and Titles. The discipline focused primarily on engineering and technological features of textile, plant engineering, instrumentation, automotive and other industry products; graphic analysis; statistical methods of data processing; study of product form and structure (historical and contemporary); and the technical implementation of the study results. Yet the history, theory, and particularly the philosophy of design remained outside the researchers’ purview. Presently in Uzbekistan little is done in terms of basic research on contemporary design.

The context of social and cultural development in Uzbekistan actualized the need for thorough academic study of design, resulting in the changed academic passport name in the registry of the State Commission for Academic Degrees and Titles. Now the “Industrial Art and Design” is changed to the “History and Theory of Design”. The change is not about the name only: it has re-focused research from engineering and technological aspects to wider issues, namely the milestones in historical development of design locally and overseas, as well as to its extensive theoretical subject-matter and practices. The discipline studies: architectural design, apparel design, graphic design, computer-aided design, advertisement design, furniture design, industrial and exhibition design, as well as art design and engineering processes taking into account ergonomic, social, psychological, environmental, biological, technological, hylological, physical and chemical factors. Many organizational issues still remain with regard to the training of design theorists, particularly in doctoral degree programs.

Master’s degree theses in Interior Design and Fashion Design defended by the graduates of the Behzad National Institute of Arts and Design offered many interesting, innovative projects that can be implemented. It was encouraging to see that the majority of the graduate students explored the experience of similar projects in other countries before taking to their own projects.

In summary we note that design in Uzbekistan certainly does exist and is constantly evolving. One can clearly see its different manifestations; there are design firms and designers working with local consumers and local products. Design in Uzbekistan is a dynamic dimension that is always changing, “providing scope for social discourse and personal associations equally” (11, p. 82). As a reminder to local designers, here is a quote from the famous American academic Keith White who truthfully said: “Admire those who came before you, but do not imitate them” (11, p. 99). It is exactly this ability that stimulates design, being its driving force and the basis for exciting projects.

References

1. Глазычев В.Л. О дизайне. М., 1970.

2. Розенсон И. А. Основы теории дизайна. Спб., 2008.

3. Лола Г. Н. Дизайн. Опыт метафизической транскрипции. М., 1998.

4. Icons of Design. Amsterdam, 2000; Thomas Hauffe. Design. Köln, 1995;

5. Charlotte & Peter Fiell. Design des 20.Jahrhundert. Köln, 2013; Bauhaus Archive Berlin. The Bauhaus Collection. Berlin, 2010; Joan Cambell. The German Werkbund. USA, Princeton university press, 1978; Hans Eckstein. Formgebung des Nützlichen. Marginalien zur Geschichte und Theorie des Design. Düsseldorf, 1985; Bernhard E. Bürdek. Design. Geschichte, Theorie und Praxis der Produkt-geschtaltung. Schweiz, 2005; Exhibition design 2 и др.

6. Аверинцев С. С. Символ. КЛЭ. Т. 6. М., 1971.

7. Лаврентьев А. Н. Визуальная культура и визуальное мышление в дизайне. М., 1990; Лисовец И. М. Дизайн и массовая культура (возможности индивидуализации мира повседневности). М., 1998; Кантор К. Правда о дизайне. М., 1996; Проблемы стилевого единства предметного мира. М., 1980; Фор Э. Дух форм. СПб., 2002; Розенсон И. А. Основы теории дизайна. Спб., 2008 и др.

8. Розенсон И. А. Основы теории дизайна. СПб., 2008.

9. Современная архитектура и дизайн. Баку, 2003; Э.Ф.Алиев. Восприятие визуальной формы в дизайне и искусстве. Баку, 2010. и др.

10. Э. Ф. Алиев. Восприятие визуальной формы в дизайне и искусстве. Баку, 2010, с. 3

11. Постановление Кабинета Министров РУз «Программа развития ландшафтного дизайна». 13 августа 2013 г.

12. Уайт К. 101 полезная идея для художника и дизайнера. СПб., 2010, с. 82.